Most of the pastors I’ve met over the years were gifted in speaking. But very few are able to listen, and fewer still are able to sit in silence with those who need company more than words. This is not to say that words don’t matter. It’s merely to point out their limits. There’s a line related to this in A Place on Earth that has haunted me ever since I first read it. Burley Coulter sends a letter to his nephew Nathan. In it, he recounts how Jayber Crow says that “the worst thing about preachers is they think they’ve got to say something whether anything can be said or not.”1 In a moment in a different novel—Jayber Crow—the protagonist actually displays the ability to provide silent comfort. I want to unpack this moment to help us think about how we ourselves can provide this sort of comfort.

“I came down and went over and sat beside Mat.”

Jayber, the town barber, describes a night in 1945. The end of the war is near, and Jayber is sitting in his barber chair, reading Thomas Hardy’s The Woodlanders on a hot night. Port William is largely quiet. But then Jayber hears footsteps, and he sees Mat Feltner looking in. Jayber invites him in. “Come in! Come in! Have a seat!”

Jayber is aware of what’s going on. “I knew what he was doing. He was walking away from his thoughts, but his thoughts were staying with him. He was tired but he couldn’t sleep.” Some time before, Mat had received news that his son, Virgil, was missing in action. Most people presume he’s dead.

Jayber and Mat begin to talk—first about what’s happening in and around Port William, then the weather. When the conversation dies down, Jayber attempts to bring it to a close:

Trying to end it, I said finally, “Well, we’ve had a time,” speaking of the weather.

And Mat said, “Yes, we’ve had a time,” speaking of the war.

Jayber then seeks to comfort Mat with words, but they fall flat. The conversation dies down again, but Mat eventually opens up about why he was out late that evening.

He had had a dream. In the dream he had seen Virgil as he had been when he was about five years old: a pretty little boy who hadn’t yet thought of anything he would rather do than follow Mat around at work. He looked as real, as much himself, as if the dream were not a dream. But in the dream Mat knew everything that was to come.

He told me this in a voice as steady and even as if it were only another day’s news, and then he said, “All I could do was hug him and cry.”

Rather than trying to say more, Jayber now simply draws closer to Mat:

And then I could no longer sit in that tall chair. I had to come down. I came down and went over and sat beside Mat.

If he had cried, I would have. We both could have, but we didn’t. We sat together for a long time and said not a word.

After a while, though the grief did not go away from us, it grew quiet. What had seemed a storm wailing through the entire darkness seemed to come in at last and lie down.

Mat got up then and went to the door. “Well. Thanks,” he said, not looking at me even then, and went away.

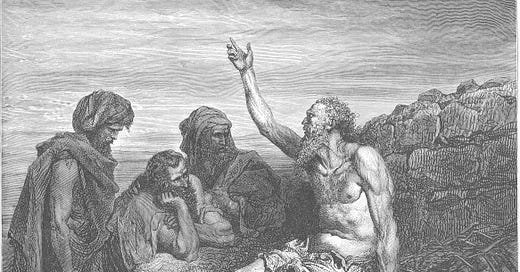

What Job’s friends do well

Job’s friends—Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite, and Zophar the Naamathite—are notorious for not providing much comfort. But they start out well: “And they sat with him on the ground seven days and seven nights, and no one spoke a word to him, for they saw that his suffering was very great” (Job 2:13, ESV).

This is what Jayber does. He came down from the barber chair to be near Mat. He sits next to him in his suffering.

And this kind of presence is so rare and so helpful. There is a quote in Dave Furman’s book Being There that highlights this dynamic. It’s by a man who has known more grief than most:

I was sitting, torn by grief. Someone came and talked to me of God’s dealings, of why it happened, of hope beyond the grave. He talked constantly, he said things I knew were true. I was unmoved, except to wish he’d go away. He finally did. Another came and sat beside me. He didn’t talk. He didn’t ask leading questions. He just sat beside me for an hour or more, listened when I said something, answered briefly, prayed simply, left. I was moved. I was comforted. I hated to see him go.2

This is what it looks like to put Paul’s exhortation in Romans 12:15 into practice: “Rejoice with those who rejoice, weep with those who weep.”

Sitting with our friends

I tend to be very much like the sort of preacher Jayber describes when he says that “they’ve got to say something whether anything can be said or not.” Over the past few months, I’ve repeatedly sat next to those who are grieving and sick, and not being sure what to say, I said too much. And this happens despite Jayber’s assessment of preachers having stuck with me for a number of years now.

I’m raising these matters to say that it is important for God’s people to be with those who are grieving, those who are sick, those who are suffering. And these moments often call for silence. This does not feel productive, of course. Not at all. But in the economy of the kingdom it is, because their suffering might grow quiet as a result. This is what we learn from Jayber coming down from his barber chair and sitting next to Mat. And readers might be reminded of a different coming down, one that was far greater and far more significant:

Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross (Philippians 2:5–8).

Of course when we do speak we want to point to what Christ has done. There is value in pointing to the fact that “the God and father of our Lord Jesus Christ” is “the Father of mercies and God of all comfort,” that Jesus repeatedly felt compassion for the crowds and wept at the tomb of his friend, and that “the Spirit helps us in our weakness” (Romans 8:26). There is a place for speaking, praying, and singing comfort over those who grieve. However, we would do well to remember that in grief, people need friends they hate to see go, those who sit beside us, listen, answer briefly, and pray simply.

The context is a pastoral visit that does not go all that well. I intend to come back to this visit in a future post, to talk about the importance of knowing our people.

Joseph Bayly, The View from a Hearse (Colorado Springs: Cook, 1969), 40–41.

The painting in this post is Gustave Doré’s Job Speaks with His Friends (Job 2:1-13) from 1866.

Thank you for this. The ministry of presence (and active listening) is hard to quantify and therefore often neglected.

My current husband of 4 years, I worked for 25 years ago when he was a pastor. He taught classes on the art of listening and including what is not being said—as well as silence. He is now in Hospice and I am so thankful to have learned what I now can give back to him. He also introduced me to Wendell Berry so it’s come full circle. Thank you.